Guide to Avoiding Common Motorcycle Auction Mistakes

lightly bent, badly jetted sportbike and a seriously bruised ego.

Since then, I’ve spent years around auctions—dealer-only lanes, public salvage auctions, online platforms like Copart and IAAI, even the occasional Bring a Trailer rabbit hole at 1 a.m. I’ve bid, lost, overpaid, scored steals, and watched a lot of people make the same painful mistakes.

This guide is exactly what I wish someone had shoved in my hand before I raised my bidder paddle for the first time.

Mistake #1: Thinking “Auction = Automatic Bargain”

When I first started bidding, I assumed everything at auction was 20–30% below market. That’s fantasy.

On popular models—think late-model Honda CBRs, Yamaha R6s, Harley Softails—bidding wars can push prices above private party value once you add fees. A 2020 R6 that looks cheap at $7,800 hammer price can easily hit $9k+ after buyer’s fees, transport, and taxes.

In my experience, the right mindset is: auction = opportunity for value, not a guarantee.

What I do now:

- I check actual selling prices, not asking prices, on CycleTrader, Facebook Marketplace, and eBay completed listings.

- I set a hard max based on total out-the-door cost, not just the bid number.

- If my limit is $6,000, I back-calculate. With a 10% buyer’s fee and ~$300 in transport, my max bid is about $5,100. If it goes past that, I’m out, no drama.

Industry data backs this up. Manheim and ADESA wholesale reports (used heavily by dealers) show late-model, clean-title bikes often sell close to retail in hot markets. The “steals” tend to be older, niche, or imperfect bikes.

Mistake #2: Ignoring All the “Small” Fees That Aren’t Small

The first time I bought from an online salvage auction, I thought I’d scored a wrecked but rebuildable café project for $1,000. When I actually did the math:

- Buyer’s fee: $250

- Internet bid fee: $79

- Gate/yard fee: $59

- Documentation fee: $75

- Transport to my city: $350

My “$1,000 bike” was suddenly flirting with $1,800. At that point, it was barely worth the sweat.

When I tested a simple spreadsheet for auction buys, my decisions got way better. I plug in:

- Estimated hammer price

- Buyer’s fee (from the auction’s fee table)

- Any internet/online premiums

- Yard, doc, and title fees

- Towing or shipping (use a quote from a shipper, not a guess)

- Expected repair costs + 15–20% buffer

If the total lands within 10–15% of clean private-party value, I pass unless it’s something truly special.

Some auction houses are notorious for opaque fee structures. I’ve found the more hidden the fees, the more likely you are to overpay. Always download the current fee schedule from the auction’s site before you bid.

Mistake #3: Bidding on Photos, Not on Reality

Online auctions make it dangerously easy to fall in love with a bike from your couch. I’ve done it more times than I’ll admit.

Here’s what photos often hide (or conveniently don’t show):

- Slightly twisted forks

- Bent subframes

- Hairline cracks in engine cases

- Dry, cracked tires

- Rotted fuel tanks on bikes that sat

- Rat’s nest wiring jobs under the seat

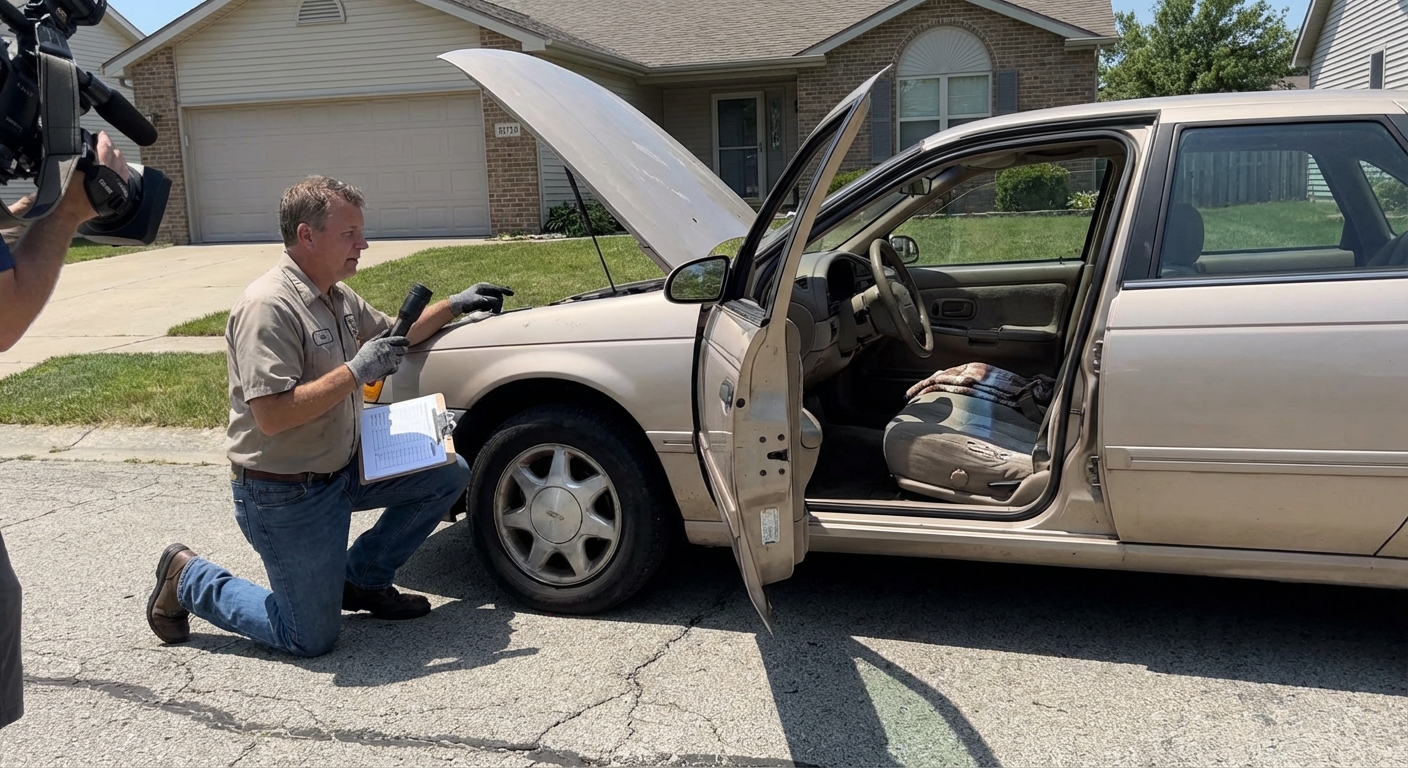

When I started forcing myself to do structured condition checks, everything changed. When I can inspect in person, I go through a quick but thorough process:

- Sight down the forks and rear subframe for alignment

- Check steering stops and triple tree for impact marks

- Spin wheels and check for wobble

- Look for overspray or mismatched fasteners (signs of cheap repairs)

- Verify that the engine at least turns over smoothly by hand or with the starter

If it’s online-only, I:

- Watch any walkaround videos at 0.25x speed and pause constantly

- Zoom into reflections to spot subtle bends

- Check for repeated auction runs (same VIN relisted = red flag)

- Pay for a third-party inspection whenever the value justifies it

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) has repeatedly reported that frame and structural damage are major contributors to motorcycle crash severity. Trying to eyeball that from four blurry photos is asking for trouble.

Mistake #4: Underestimating Salvage and Title Nightmares

The salvage game looks sexy: cheap crashed bikes, big rebuild potential. I went hard into this a few years back and learned quickly that the title is often more dangerous than the damage.

Common traps I’ve personally hit:

- Salvage vs. certificate of destruction: One can be rebuilt and titled; the other is basically parts-only in many states.

- State-specific rules: A bike that can be retitled in one state might be nearly impossible in another.

- Inspection surprises: I had a rebuilt bike fail inspection because of a missing OEM reflector… after a 3-month wait.

Now I always:

- Check my state DMV/DoT guidelines on salvage and rebuilt titles before bidding.

- Verify whether the auction is selling with a transferable title, bill of sale only, or non-repairable status.

- Factor in inspection fees, potential re-inspection, and months of down time.

In my experience, salvage bikes make sense if:

- You’re comfortable wrenching yourself.

- You’ve got access to reasonably priced parts or donor bikes.

- You’re OK with the resale being 20–40% lower than a clean-title twin.

If you’re buying your first or only bike, I’d strongly lean toward clean titles unless you’re very mechanically and paperwork-savvy.

Mistake #5: Getting Caught in Auction Hype

Auctions are designed to mess with your brain. Fast talk, countdown timers, other bidders raising paddles like it’s free… it’s intoxicating.

One night at a dealer-only sale, I watched a ratty 15-year-old cruiser with oil leaks and mismatched tins go for almost retail money because two bidders decided they “weren’t losing.” I’ve been that person.

When I tested a simple psychological trick—decide your walk-away price and write it on paper before the lot starts—my overbids basically disappeared.

What I do now:

- I set my max bid when I’m calm, not in the heat of bidding.

- I literally leave the lane or close the browser the second bidding passes my number.

- If I lose a bike, I force myself to wait 24 hours before bidding on anything else.

There’s always another auction. There’s only one of your bank account.

Mistake #6: Skipping VIN Checks and History

Early on, I bought a clean-looking Kawasaki at auction that turned out to have a prior salvage history in another state that wasn’t disclosed in the listing. It was technically legal—but a nasty surprise.

Now I run VIN checks religiously through services like:

- NICB’s free VINCheck for theft and total loss

- Commercial history reports for title brands, mileage issues, and prior salvage

I’ve seen bikes that were:

- Stolen and recovered

- Exported and re-imported

- Odometers rolled back

- Branded as flood-damaged years before showing up at auction as “normal” repossessions

A five-minute VIN check has saved me thousands more times than I can count.

Mistake #7: Forgetting the Real Cost of Repairs

If you’re like me, you’ve probably told yourself, “I’ll fix it cheap; I’ll source used parts.” Then you price a single OEM fairing panel or a modern ECU.

When I rebuilt a lightly crashed naked bike, I thought I’d be clever:

- Used handlebars: cheap

- Replacement controls: not too bad

- Bent radiator + bracket + coolant + labor: painful

My parts bill ended up 40% higher than my optimistic estimate. And that was without paying shop labor.

How I handle it now:

- I price the top 5 obvious parts before bidding (forks, wheels, plastics, tank, major controls).

- I assume small stuff—bolts, clips, fluids, random gaskets—will add another 15–25%.

- If I’d need to pay a shop more than 5–6 hours of labor, I walk unless the deal is truly insane.

The American Motorcyclist Association and multiple dealer techs I’ve spoken with all say the same: modern bikes are safer and more sophisticated, but also more expensive to put right after a crash.

Mistake #8: Not Matching the Bike to Your Actual Needs

This one’s less technical but just as costly.

I once grabbed a track-prepped 600 at auction because it looked like a rocket and the price was silly low. Race plastics, slicks, safety wired… the whole deal. For a dedicated track toy, it would’ve been perfect.

I needed a commuter.

I spent months trying to “de-race” it—lights, mirrors, wiring harness fixes, gearing changes—only to eventually sell it and buy a boring but brilliant commuter standard. If I’d been honest about my use case, I’d have skipped that lane entirely.

Now I always ask myself:

- Is this bike right for street, track, commute, touring, or weekend twisties?

- Will I actually use this the way it’s set up right now?

- Am I secretly trying to buy an identity instead of a motorcycle?

When the bike matches the role from day one, you’re way less likely to regret the hammer falling.

A Simple Checklist Before You Bid

What’s worked best for me over the years is a quick mental (or written) checklist before I bid on anything:

- Market value known? I’ve checked real selling prices, not wishful asking numbers.

- Total cost calculated? Fees, transport, repairs, and a buffer are built into my max.

- Title status clear? I know the title brand and my state’s rules on it.

- History checked? I’ve run the VIN through at least one reliable database.

- Condition understood? I’ve inspected in person or paid for an inspection when it matters.

- Use case honest? This bike actually fits my real life, not my fantasy life.

- Walk-away price set? I’ve decided my ceiling and commit to stop there.

When I stick to this, I don’t just save money—I actually enjoy the auction process.

Motorcycle auctions can be an incredible way to get into riding, flip bikes, or pick up projects. They can also be a fast track to owning a broken machine you resent every time you look at it.

The difference, at least in my experience, isn’t luck. It’s preparation, brutal honesty with yourself, and the discipline to let a “deal” go when the numbers or the story don’t make sense.

Sources

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) Motorcycle Safety - Official data on motorcycle crashes and safety factors

- NICB VINCheck - Free theft and total loss database for checking vehicle history

- U.S. Department of Transportation – State DMV Links - Gateway to state-specific title and salvage regulations

- American Motorcyclist Association – Buying a Used Motorcycle - Practical guidance on used bike evaluation and ownership

- Manheim Market Report - Industry wholesale pricing data used by dealers to assess auction values